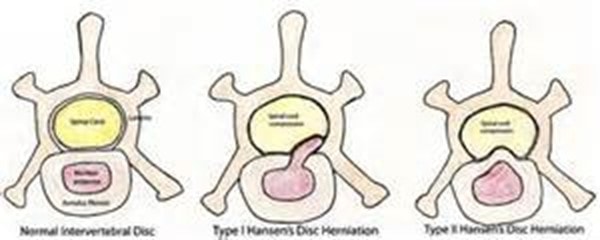

Disc disease occurs when pathology affects the intervertebral discs – the soft tissue spacers found between vertebrae of the spinal column. The intervertebral discs are a bit like doughnuts with a fibrous surround (the annulus fibrosus) and a gel centre (the nucleus pulposus).

Nerve roots come out between vertebrae, and these can easily be affected by pathology of the discs that sit just below them.

Certain breeds are notorious for developing intervertebral disc disease. These breeds are often the long-backed/short-legged breeds that are congenital achondroplastic dwarfs and include Dachshunds, Basset Hounds and Shi Tzus. They are often affected between 2 and 5 years of age, and it is pretty common to see the same dog return with problems with another intervertebral disc a few months later. That said, disc disease can be seen in just about any breed and at a wide variety of ages.

There are 7 cervical vertebrae (C1-7). There are no discs between the skull and C1 or C1 and C2. There are 13 thoracic vertebrae (which support the ribs), 7 lumbar vertebrae, and three sacral vertebrae (which are fused into one bone called the sacrum). Discs often become problematic at areas where high-motion parts of the spinal column (the cervical and lumbar zones) meet the less mobile parts of the spinal column (thoracic and sacral). There is, relatively speaking, plenty of space around cervical spinal cord within the cervical spinal canal and around the lumbar spinal cord within the lumbar spinal canal. So most surgical management of disc disease (around 80%) occurs at the half dozen or so spaces around the thoracolumbar junction (T11-L3). The remaining surgical cases typically involve the lower cervical and the lower lumbar disc spaces.

When disc disease occurs, the spinal cord can impinge. This causes neurological signs affecting the body on the tail side from the injury but not the body on the head side from the injury. Nerve roots can also be trapped, and this can cause neurological signs affecting the areas that those nerve roots serve. Nerve root entrapment typically causes significant pain.

The spinal cord, sitting above the intervertebral discs, can be:

- Contused. The spinal cord gets injured as disc material impacts on it.

- Compressed. The cord is a delicate soft tissue structure that is situated within a boney box (the spinal canal of the vertebrae)

Disc disease is classified as:

Type 1.

These are disc “extrusions “, where the jam of the disc “donut” oozes out through a defect in the fibrous “dough”. These cause signs through a mixture of contusion and compression. Can often have dramatic neurological signs but can often do well with surgery. For anatomical reasons, discs usually extrude to the left or right. Sometimes the disc material can travel a way up or down the spinal canal or around the spinal cord to sit at the side or even occasionally above the cord. But it often sits in a clump under the spinal cord at the level where it extruded. Type 1-disc lesions most often occur in chondrodystrophic dogs like Dachshunds.

Type 2.

These are disc “protrusions” where the annulus bulges out, but the jam of the doughnut stays within the dough. These often have gradual and progressive signs. These are compression rather than contusion injuries, and they usually occur over time – i.e. they are “chronic”. Signs are often less severe than is the case to type 1 injuries, but because these are chronic injuries, the response to surgery – the recovery of the spinal cord – is often less predictable.

Type 3.

These are low volume, high-velocity injuries where a small piece of disc material extrudes and impacts the spinal cord with contusion but negligible compression. These are not surgically treated because the aim of surgery is to reduce compression, and this isn’t a significant feature in type 3-disc disease.

The neurological signs that we see depend on the level of the injury and how badly the neurological structures are compromised.

At West Midlands Veterinary Referrals we've grade the severity of the signs of disc disease as follows:

- Grade 1/5. These are painful but not there are not neurological signs.

- Grade 2/5. These are painful and wobbly, but they are still able to walk in a fashion

- Grade 3/5. These are painful and wobbly to the point that they can’t walk. The limbs still have voluntary movement, meaning that the intention to walk is still being transmitted to the legs past the level of the injury, and the legs make some effort to move in response. Some of these cases are unable to urinate on their own.

- Grade 4/5. There is no voluntary movement present in the legs downstream of the injury. A deep pain sensation is still present, though. When we pinch the toes, the head reacts/turns and clearly knows about what we’ve done. There is still some functional link across the site of the injury.

- Grade 5/5. There is no voluntary movement and no deep pain sensation, even when we pinch the toes with instruments.

The forelimbs and hind limbs will be involved when the cervical discs are affected. Grades 1-3 at this level are called quadriparesis. Grades 4-5 would be called quadriplegia, but the loss of voluntary movement at this high spine level would almost certainly be fatal as the ability to breathe by moving the diaphragm muscle would be lost. The hind limbs alone will be affected when the problem is further down the spine. The systems required for breathing are not affected and so the severity of the injury to the cord can be much worse without being fatal. Grades 1-3 are called paraparesis, and grades 4-5 are called paraplegia.

Medical management of disc disease involves strict rest, usually meaning a cage for at least 3-4 weeks, anti-inflammatory treatment and analgesia (pain medication) as required. Symptoms may improve as the damage caused by contusion repairs and as inflammation and swelling subside, aided by rest and medication. Some medically managed patients can suddenly deteriorate, requiring a rapid change to “plan B” and surgery. We have seen grade 2/5 cases deteriorate to grade 4/5 overnight while confined in a cage.

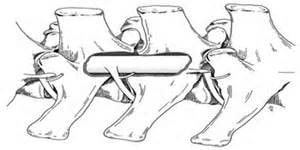

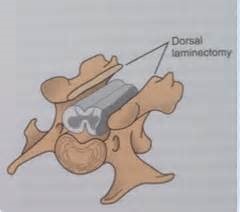

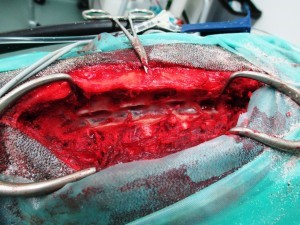

Surgical management involves decompression of the injury. Imaging is required to localise exactly where the injury is – at what level of the spine and whether there is compression predominantly to the left or to the right. Bone is then removed surgically to allow access to the spinal canal to remove the extruded or protruded disc material.

Common decompressive surgeries are ventral slots (for cervical disc disease), hemi-laminectomies (for thoracolumbar disc disease) and dorsal laminectomies (for lumbo-sacral disc disease).

Urinary management aims to keep the bladder decompressed where required in patients that have the more severe grades of disease or in surgical patients awaiting improvement in signs after surgery. If pets can’t voluntarily urinate for themselves because of their neurological status, the bladder will fill and fill until the stretching of its walls results in lasting damage.

The bladder can be emptied by:

- Pressing across the body wall. This can be relatively easy, or it can be very difficult. Some owners with amenable and chilled pets can be taught to do this. But it is a skill, and it is quite possible to rupture the bladder inside the abdomen with inappropriate technique.

- Catheterisation. The intermittent placement of catheters in males is usually straightforward, and we often train owners how to do this. In females, it is not so easy. Placement of an indwelling catheter is possible but usually results in urinary tract infection (UTI).

Imaging involves:

- X-rays – General anaesthetic is usually required to get well-positioned images. Simple X-rays are of minimal use on their own. Narrowed disc spaces and mineralised intervertebral discs can give a clue as to the location of the problem, but x-rays are rarely enough to allow surgery, and even if a problem can be seen/suspected with X-rays, other imaging is required to confirm and to check for injuries at other intervertebral spaces.

- Myelography – General anaesthetic is required. A contrast agent is injected into the fluid around the central nervous system using a needle introduced just behind the skull or, more commonly, just in front of the pelvis. There are small risks associated with myelography over and above the risks of the GA. The risks of myelography are often outweighed by the ease and speed with which a myelogram can direct a surgical approach. Myelography is not as sensitive in indicating problems at the spinal canal's lower end.

- Advanced imaging – General anaesthetic is required. CT myelography or MRI scans are excellent but much more expensive and less widely available than myelography. Advanced imaging gives more information on the spinal canal's soft tissues and boney structures than myelography.

How is prognosis affected by medical versus surgical management?

The difference in outcome between medical and surgical treatment is not expected to be significant in grades 1 and 2, so medical treatment is usually advisable. Surgery is reserved for cases that haven’t responded within a few weeks or where the pain is unmanageable. 90-95% of grade 1-2 cases are successfully managed by “success” we mean an outcome where the patient is comfortable, continent, and capable of getting around on their legs (although they may not be neurologically normal and may still look a little drunk).

Surgically managed grade 3 cases usually do as well, though the success rate in medically managed ones begins to disappear. At grade 4, only about half of the medically managed ones will be successful, whereas 90% of the surgically managed ones will be. At grade 5, there is negligible hope of success with medical management and about half of the surgically managed ones will get better. Where dogs have become grade 5 (“deep pain negative”) very quickly, the outcome is less likely to be good. This is because the sudden signs suggest contusion predominates over-compression, and surgery is less likely to be helpful. Compression injury predominates over contusion when the patient becomes deep pain negative over a few days. So the outcome of surgery is more likely to be favourable SO LONG AS SURGERY OCCURS WITHIN HOURS OF THE PATIENT BECOMING DEEP PAIN NEGATIVE.

It can be challenging to decide between medical management or surgical management of grade 2-disc disease sometimes.

Factors include:

- Finance and other time commitments that the owner has. Owners have the lives and situations they have, and if there is no means of providing proper aftercare to give a reasonable chance of success, then it is often wise to admit that sooner rather than later.

- The compliance of the patient (a dog that lets you catheterise it with a wag of the tail makes a much better candidate for surgery than one that tries to bite you!)

- The ultimate prognosis – owners need to think very hard before embarking on surgery for a grade 5 case. This is definitely a time to listen hard to the head and heart.

- The ease with which the patient’s bladder and urinary output can be managed in the post-op period.

- The ease with which the patient can be lifted in the post-op period

Here are some cases to highlight some of the issues:

Fudge was a small dog with grade 2 disease (“walking but wobbly”) and a breed, age and pattern of signs that made it extremely likely that there had been a type 1 disc extrusion in the thoraco-lumbar region of the spine. Fudge was small, easy to handle and there were some financial constraints, so the owners chose to opt for medical management. They diligently confined Fudge to a cage for 3-4 weeks and he made excellent progress. Had his signs deteriorated, he was small enough to be easily carried and lifted, and the plan could then easily have been changed from a medical to a surgical one.

The drummer was a Weimaraner, a sizeable 10-year-old dog with grade 2 paraparesis. He was still walking (though very wobbly and getting his back legs tangled up), but his signs were progressive – they were getting worse. He was also of age and breed where disc disease was less likely, and the possibility of cancerous disease was a definite consideration, especially so since signs were progressive. It was very desirable that he didn’t get any worse because lifting a dog that weighted well over 40 kg, even an “easy” compliant dog like Drummer, would have been a nightmare or even impossible for the owners. So, a decision was made to go for early imaging and surgery. A lumbar puncture myelogram clearly indicated compression of the spinal column on the left side at L3-4. Surgery yielded HUGE amounts of extruded disc material and he went home the same day as the surgery, able to walk and urinate on his own. Result!

It is a widespread finding that owners grossly underestimate the emotional roller-coaster that they will have to ride in the weeks following spinal surgery. Owners typically surf a wave of optimism and adrenalin when they are told their pet has at least a chance with surgery. But after this ebbs away, waiting to know if the outcome will be successful can be extremely draining. Surgery, even with us, is not cheap, and the rounds of physio, assisted lifting and urinary management, and later hydrotherapy takes a lot of time, planning and organisation.

Jasper was a Doberman who presented with grade 3 cervical disc disease. His signs were pretty serious pre-op – if they’d been much worse, he’d have lost the ability to breathe, and that would have been that. He had a myelogram and decompressive surgery of the cervical disc space. This large but easy-going dog was fortunate to have the owners that he had. We were nothing short of awestruck by the time and effort that they put into his aftercare. They work with horses and are used to being around big clumsy things! There were fit, strong people around to lift Jasper. With a bit of guidance, they constructed a superb physio frame. Jasper was then lifted into this umpteen times daily for massage, passive flexion, extension exercises, and physiotherapy. With the frame and sling stopping him from falling, he could take some of his own weight regularly, and that helped maintain muscle mass. It took weeks, but he made slow steady progress and the owners never lost heart and they got the outcome that they and Jasper deserved.

Grade 5 signs with disc disease need a lot of thinking through before rushing into surgery – but there is no time available. Generally, a decision needs to be made there and then, imaging and surgery with a very guarded prognosis, or euthanasia.

Rusty was a Staffordshire Bull Terrier that presented with grade 5-disc disease due to thoracolumbar disc disease with loss of use of the hind limbs. He could not feel his toes, even with firm pressure applied by a pair of pliers. We urged the owners to consider euthanasia, but they made a fast and clear decision to go for myelography and surgery. The surgery went very well and when he had deep pain sensation the next day, we were pretty sure that Rusty and his owners were going to get lucky! He made steady progress, getting back on his feet in 3-4 weeks. We were delighted to have been proven wrong in having advised euthanasia! But the chances of Rusty ever walking again had only been 50:50 at best and the owner did need to hear this at the outset before surgery, “loud and clear”.

Sammie (not his real name) was a 4-year-old Dachshund that presented with grade 5-disc disease due to thoracolumbar disc disease with loss of use of the hind limbs. The owners were advised to have him euthanized, but they elected myelography and surgery and to catheterise him twice daily post-op. He never recovered to being able to walk and the owners tried him in a cart. After six months, they came to have him euthanized, and although we know they’d made their decisions for the best of reasons, they regretted not opting for euthanasia at the outset of signs.

Roman, a 6-year-old Dachshund had grade 3-4/5 signs affecting the hind limbs suggesting thoraco-lumbar disc disease when he came to us. He had initially been (very reasonably) conservatively managed for a week by his own vet with grade 1-2/5 spinal signs. Unfortunately, his signs had then progressed. The prognosis for eventual “success” with myelography and surgery was still considered reasonably good. It was estimated at 90%, with “successes defined as comfortable, continent and capable of decent mobility, but not necessarily a return to neurological normality. The myelogram suggested disc disease at T11-12. Lateralisation was difficult, even with oblique views, but left sided compression was thought to be the most likely. A left and right T11-12 hemilaminectomy and a left-sided T11-12 fenestration were performed. A disappointing yield of disc material was retrieved, but the area was now known to be decompressed. He made plodding progress post-op, and we doubted he would ever get to his feet. Six months later, the owner reported that he scooted about happily on his bum but could get to his feet and had just regained the ability to urinate independently. This case clearly illustrates the point that 90% is not 100%, they don’t all get better, and those that do, don’t do it quickly or to a level that every owner would be satisfied with as a “successful” outcome.

Carts can be used for dogs, but generally speaking, at West Midlands Veterinary Referrals, we don’t think these are a great idea for most dogs. That having been said, some dogs, typically the smaller dogs with a “can-do” attitude, can do well in carts.