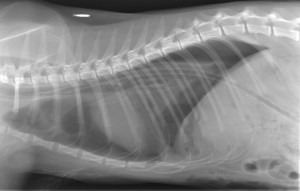

After trauma like road traffic accidents, ruptured diaphragm can occur and abdominal contents including intestines and liver can move through into the chest cavity. The reduced volume available for the lungs usually leads to significant respiratory distress. Occasional cases however have surprisingly minimal clinical signs.

These cases can be a challenge. The diaphragm is often relatively straightforwards to repair, though some can be tricky. The challenge is for the anaesthetist to keep the patient well ventilated under anaesthetic while the surgery proceeds. Once the surgery is underway, the patient can’t breath for itself and a bag is used to push air into the lungs under gentle positive pressure. We use a range of aids to anaesthetic monitoring in both our operating theatres including capnography (monitoring expired CO2 levels); pulse oximetry (monitoring oxygen carriage in blood and pulse rate); Electrocardiography (ECG, monitoring heart electrical activity); monitoring body temperature. These aids are all well and good, but they are an aid to, and not a substitute for, experienced Registered Veterinary Nurses doing direct patient monitoring with eyes, ears and fingers.

The prognosis for ruptured diaphragm is usually good, though occasional cases have problems as the lungs re-inflate. This is especially true of cases where the rupture has been present for a long time before surgery. Over 90% of cases go on to make a full recovery.

31st October 2013